Continuation of the review of the best cover crops. The previous article covered cereal and cruciferous cover crops : general characteristics of the type and a detailed look at some of the most effective green manures. Now, let’s consider legume cover crops.

Traditionally used legume cover crops include:

- Winter annuals (lupine, crimson clover, hairy vetch, field pea, etc.)

- Perennial legumes (red clover, white clover, lupine, alfalfa, sainfoin).

- Biennial legumes (sweet clover).

Main tasks of legume cover crops:

- Nitrogen accumulation (fixation) from the atmosphere.

- Soil erosion control.

- Biomass production for organic matter return to the soil.

- Attraction of beneficial predatory insects.

How Do Legume Cover Crops Differ from Others?

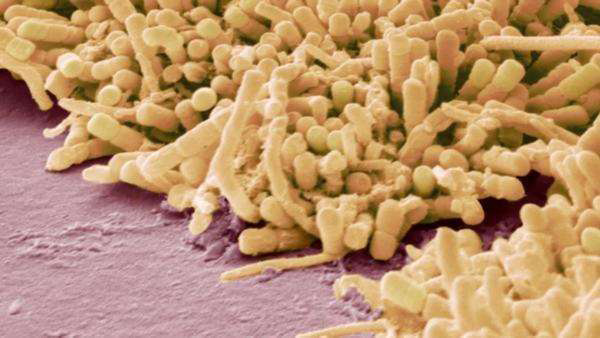

Legume plants form partnerships with specific bacteria called Rhizobia. These are nitrogen-fixing nodular bacteria capable of capturing nitrogen from the air and sharing it with the plants they inhabit.

Legumes vary widely in their cover crop abilities. Professor Dovban, in his monograph on the productivity of narrow-leaved lupine ( 1 ), states that lupine has the highest nitrogen-fixing capacity (atmospheric nitrogen, up to 95% of the total nitrogen mass in the biomass). Detailed information on lupine is provided below.

Legumes sown in the fall accumulate most of their biomass in the spring. Sowing should start earlier than for cereals so that the legumes can establish good root systems before frost. Perennial and biennial legume green manures can be combined with various crops, growing between rows. Generally, legumes have a lower carbon-to-nitrogen ratio than grasses, so they decompose faster and contribute less to humus compared to carbon-rich plants.

Mixtures of legumes and cereals combine the advantages of both types, including biomass production, nitrogen fixation, weed suppression, and soil erosion control.

Crimson Clover

Other names: scarlet, Italian, crimson, meat-red. Type: perennial, annual. Tasks: source of atmospheric nitrogen, soil formation, erosion prevention, living mulch (especially between rows), forage crop, honey plant. Mixtures: cereals, ryegrass, red clover.

With its rapid and sustainable growth, perennial crimson clover provides early crops with nitrogen and suppresses weeds. It is popular in North America as a forage crop and a resilient green manure. It grows well in mixtures with other clovers and oats. In California, clover is grown in gardens and nut orchards due to its shade tolerance. The flowers of crimson clover provide shelter for beneficial predators.

Cultivation: Grows well in sandy loam and well-drained soils. It poorly develops and suffers in excessively acidic, heavy clayey, or waterlogged soils. Established clover thrives in cool, moist conditions. A lack of phosphorus, potassium, and a pH below 5.0 halts nitrogen fixation. For winter, sow crimson clover 6-8 weeks before the first frost. Spring sowing should be done when the weather is fully settled, and the risk of persistent frosts has passed. Clover germinates unevenly; firm seeds need enough moisture to sprout.

Incorporation: Mowing at an early bud stage kills the plant. The root does not cause problems during incorporation. Maximum nitrogen will be available before seeding, at the late flowering stage. After incorporation, wait two to three weeks before sowing crops, as legumes increase the concentration of specific bacteria in the soil – Pythium and Rhizoctonia, which decompose organic matter. These bacteria can attack crops at peak activity.

Hairy Vetch

Other names: hairy vetch, woolly pea.

Type: winter annual, annual, biennial. Tasks: nitrogen source, weed suppression, soil drainage and loosening, erosion control, shelter for beneficial insects. Mixtures: clover, buckwheat, oats, rye, and other cereals.

Few legumes can compete with hairy vetch in terms of nitrogen contribution and biomass production. A winter-hardy, widely adapted legume, its roots continue to develop even in winter. If not supported by another crop, its cover height will not exceed 90 cm, but if its vines are spread out – up to 3.5 m! Incorporating the biomass of vetch can be challenging, but it excels in weed suppression and atmospheric nitrogen fixation. Hairy vetch is the most widely used legume cover crop on American fields (there are many good field studies).

Hairy vetch retains soil moisture both as living mulch and when incorporated, due to its lush green growth. A comparative study by the Maryland Institute showed that vetch is the most profitable legume (test before planting corn), outperforming clover and Austrian pea (Lichtenberg, E. et al. 1994. Profitability of legume cover crops in the mid-Atlantic region. J. Soil Water Cons. 49:582-585.). Hairy vetch saves on fertilizers and pesticides, increases the yield of subsequent crops due to soil formation, chelated nitrogen, promoting soil microflora development, and mulching.

The fibrous root system of vetch is enormous, creating macropores for moisture infiltration into soil layers after decomposing plant residues. Where water retention is undesirable, sow cover crop mixtures – oats and vetch is a classic, proven combination. Rye can also be added.

Vetch produces very little humus as it decomposes very quickly and almost completely (it contains little carbon, like most legumes). The carbon-to-nitrogen ratio: 8:1 to 15:1. Rye has a ratio up to 55:1. Vetch is more drought-resistant than other legume cover crops.

Hairy vetch competes with weeds through vigorous spring growth. Allelopathic effects are weak and safe for crops but create a dense, shady cover for weeds. A mixture of rye/crimson clover/vetch provides optimal weed control, better erosion protection, and more nitrogen. Rye in this mixture also supports the sprawling vetch.

Vetch accumulates more phosphorus than clovers, so it makes sense to fertilize it – it will give it all back to fruit crops later.

Cultivation: Prefers soil pH from 6.0 to 7.0, survives at pH from 5.0 to 7.5. Sow on moist soil, as dry conditions hinder its germination. Sowing can be done at any time of the year: 30-45 days before frost for early spring emergence, early spring, or July for fall incorporation. It has high requirements for phosphorus, potassium, and sulfur. Vetch can be sown with corn and sunflower (sunflower should have 4 true leaves to prevent vetch from suppressing it).

A mixture of rye and vetch softens the effects of both cover crops, fixing excess nitrogen and other nitrates, stopping erosion, and suppressing weeds.

Spring sowing of vetch yields less biomass than winter sowing.

Incorporation: The method of incorporating hairy vetch depends on the tasks it needs to solve. Incorporating vetch biomass provides maximum nitrogen but requires effort. Leaving residues on the soil surface retains moisture and prevents weed growth for about 3-4 weeks, but significant nitrogen loss occurs from the above-ground plant parts. The closer vetch is to maturity, the more nitrogen it has, and the harder it is to process and incorporate. Mowing vetch at ground level at the flowering stage kills the plant. Winter-sown vetch should not be disturbed. Typically, spring-sown vetch is not allowed to grow for more than 2 months.

Clover attracts beneficial insects and provides them with shelter. Several varieties of red clover produce different biomass yields and have varying maturity rates. Mammoth clover (late-blooming) grows slowly and is sensitive to mowing. Medium red clover grows quickly and can be mowed once in the first year of vegetation and twice in the following year. Sensitive to phosphorus, clover brings it up from the deeper layers of soil and stores it, making it available for cultivated crops after being plowed under and decomposing.

Cultivation: Red clover germinates on the 7th day in cool spring—faster than many legumes, PH: 5.5-7.5 (tolerates a wide range of soil conditions). Seedlings develop slower than vetch. It does not require deep planting (up to 2.5 cm). It is best to plant as green manure, considering its biennial development since it accumulates the maximum amount of nitrogen by mid-bloom in the second year. It does not grow longer than five years, producing the most biomass and nitrogen in the second year of vegetation. Clover seeds are often stratified directly on the snow before thawing. Clover can be sown with fertilizers. For active growth, clover needs a temperature of at least 15°C.

Plowing: To reach nitrogen maximum, clover should be plowed under around mid-bloom in the second year of vegetation. It can also be plowed earlier. For mulch under fall vegetables, mow before seed formation. Summer mowing will weaken clover before fall incorporation—this might be important if plowing is done manually (clover can be challenging to manage).

Clover often becomes a weed due to easy self-seeding. It has a parasite mite that targets gooseberries.

White Clover

Type: perennial, long-lived, overwintering annual. Uses: living mulch, erosion control, attracting beneficial insects, nitrogen fixation.

White clover is the best living mulch for interrows, under shrubs, and trees. It has a dense, fine root system that protects the soil from erosion and suppresses weeds. White clover thrives in cool, moist conditions in shade and partial shade, growing better with mowing. Depending on the variety, it grows between 15 and 30 cm.

White clover has numerous cultivated varieties that were initially developed as fodder crops. It thrives best in soils rich in lime, potassium, calcium, and phosphorus but tolerates adverse conditions better than its relatives. The longevity of clover is tied to its creeping root system, so it’s necessary to control the spread of this green manure. It is highly resistant to trampling, restoring the looseness of well-worn garden paths and alleys. It does not compete with cultivated plants for light, moisture, or nutrients because it grows slowly and densely in their shade during root development and is resistant to most herbicides.

Cultivation: White clover withstands short floods and droughts. It grows in a wide range of soils but prefers clay and loam. Some varieties were bred for sandy soils. If clover is to germinate in unfavorable conditions (drought, excessive moisture, or plant competition), the seeding rate should be increased. Growing white clover “for winter” should begin in mid-to-late August so that the plant has time to root well (no later than 40 days before the first frost). Sideral mixtures of white clover with grasses reduce the risk of legume loss from frost. Spring sowing is possible alongside the planting of cultivated plants.

Plowing: This clover variety is valued for soil restoration through living mulching, so it’s better to mow it, leaving 7-10 cm, rather than plowing this green manure under. For successful overwintering, the plant should be at least 10 cm tall before the first hard frost.

If clover needs to be eradicated in a certain area, it must be plowed, uprooted, or treated with a cultivator. Suitable herbicides may be used. Frequent root-level mowing does not kill the plant. If you want your seeds, collect them when most flowering heads have turned light brown.

Narrow-leaved Lupine

Type: annual, perennial. Uses: nitrogen fixation, maintaining and restoring natural soil fertility, erosion control. Challenges: low germination.

Much research on lupine has been done by Belarusian and Russian scientists. I will describe narrow-leaved lupine using information from this 2006 monograph and the book “Green Manure in Modern Agriculture” by K.I. Dovban.

In English-language agricultural resources, lupine is rarely mentioned as a green manure—vetch and clover hold the place of honor. References are more often made to European experience in lupine cultivation. Russian and Belarusian scientists work on the breeding and biology of this legume. You can learn more about lupine varieties on the Lupine Research Institute’s website .

Lupine’s root system releases enzymes capable of converting insoluble phosphorus compounds into chelated forms for subsequent crops. Lupine’s taproots loosen the soil, improving gas exchange and preventing the leaching and migration of chemical elements into groundwater (which is crucial in conditions of fertilizer overuse). Lupine has an increased need for sulfur, and the application of sulfur-containing fertilizers positively affects its biomass yield.

K.I. Dovban notes a record nitrogen accumulation by perennial lupine—385 kg per hectare, compared to red clover’s 300 kg, which is 25% more than in manure.

Cultivation: Does not grow in alkaline soil (parsley, which can be used as green manure, thrives on alkaline soil). Perennial varieties are recommended for sowing at the end of October, so they do not sprout before frost. This is a heat-loving plant, but lupine seeds can germinate at +2+4°C, with the most favorable temperature being +9+12°C. Sowing is done when the soil has warmed to +8+9°C, in rows with row spacing of 10-15 cm (up to 45 cm, which improves the development of each bush but complicates weed control between the rows), with 10 cm between seeds. The furrow depth for sowing is 4 cm.

Seedlings are frost-resistant to -9°C. Self-pollinated. Does not tolerate shading well, and the length of daylight directly affects lupine’s vegetation and fruiting. Small seeds with hard shells have difficulty germinating. In industrial settings, scarification of lupine seeds is carried out; at home, such seeds are rubbed with coarse sand. Lupine germinates well with consistent spring moisture and the use of growth stimulants. It thrives in well-moisturized sod-podzolic soils; perennial varieties conquer even the poorest, uncultivated lands (provided there is good moisture).

The strong root system of perennial lupine penetrates beneath the plow layer and accesses hard-to-reach phosphorus compounds, magnesium, calcium, and potassium. It does not require additional mineral fertilizers (this is a quote from Dovban’s book, though the monograph devotes several pages to fertilizer application). Narrow-leaved lupine is a relatively early-maturing legume green manure (88-120 days, though popular sources often mistakenly say 50 days).

The aforementioned monograph “Productivity of Narrow-leaved Lupine” describes issues with legume nitrogen fixation and the inefficiency of inoculation (artificial infection of seeds and soil with nodule bacteria). If you want to study this question more deeply, review the original source. In Dovban’s book, page 108, the work of nodule bacteria is described in detail (the book is freely available).

Plowing: Annual lupine is plowed under during or by the end of flowering. Sown in winter, lupine accumulates green mass for green manure for late potato planting or tomato planting. Perennial lupine can be mowed during the first year of vegetation but should not be plowed under—allow nodule bacteria to spread and roots to grow. Plowing should occur at least by the 2nd or 3rd year. To avoid self-seeding, flower spikes can be removed, or better yet, lupine should be mowed and plowed into vacant beds or under fruit trees, or the greenery should be added to compost.

As lupine produces a lot of juicy greenery, its plowing can be difficult manually. If you have a garden shredder and cultivator, there are no problems.

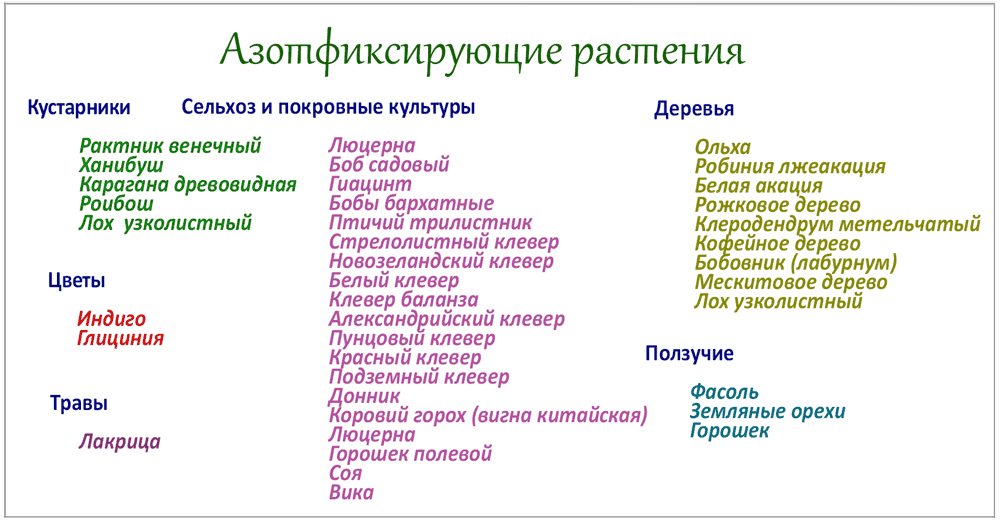

List of Nitrogen-Fixing Plants

Shrubs: Scotch Broom, Honeybush, Caragana, Rooibos, Russian Olive.

Flowers: Indigo, Wisteria.

Fruit Crops and Groundnuts: Andean yam bean, all legumes, peanuts.

Herbs: Licorice.

Trees: Alder, Black Locust (False Acacia), Carob, Peanut Butter Tree, Coffee Tree, Laburnum, Mesquite Tree, Russian Olive.

Agricultural and Cover Crops (Green Manures): Alfalfa, Fava Bean, Hyacinth Bean, Velvet Bean, Birdsfoot Trefoil, Arrowleaf Clover, Balansa Clover, Berseem Clover, Crimson Clover, Red Clover, New Zealand Clover, White Clover, Subterranean Clover, Chickling Vetch, Corn Spurry, Cowpea, Crown Vetch, Field Pea, Fenugreek, Flaxleaf Fleabane, Clustered Medick, Kidney Vetch, Lentil, Lupine, Hairy Vetch, Purple Vetch, Vetchling.