Different continents and climate zones have their answers to which cover crops are best, but there are green fertilizers that work well everywhere. Cover crops can be broadly divided into legumes and non-legumes. Each group serves its purpose, has its own characteristics, and some drawbacks.

This article reviews the best grasses and cruciferous cover crops. In the next article, I will write about the best legumes . Information sources are listed at the end of the article.

Productivity and Tasks of Cover Crops

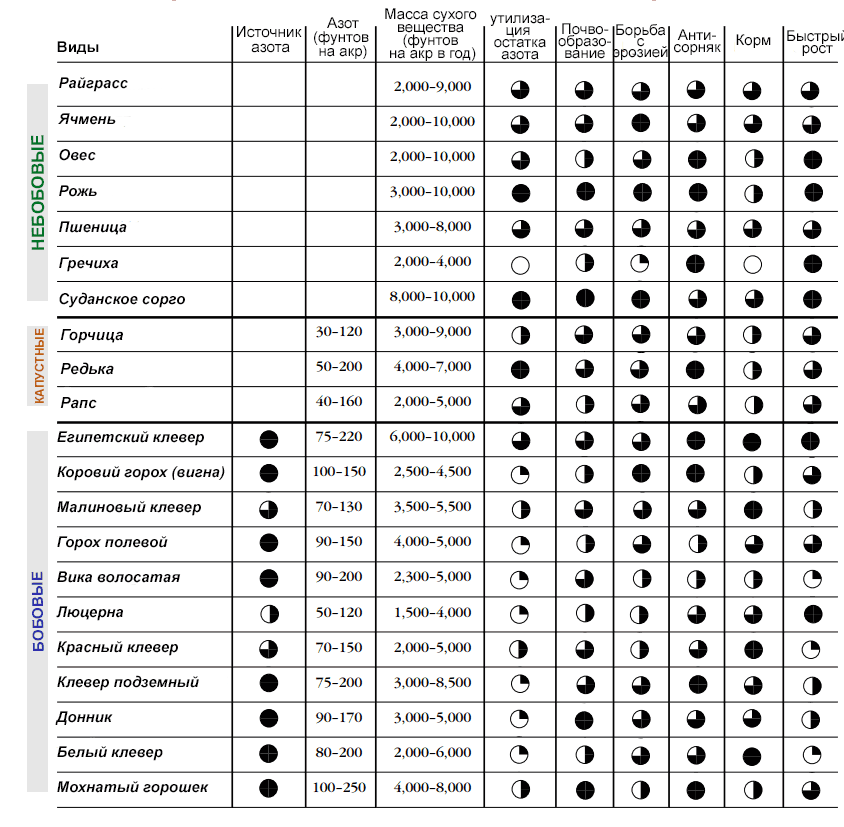

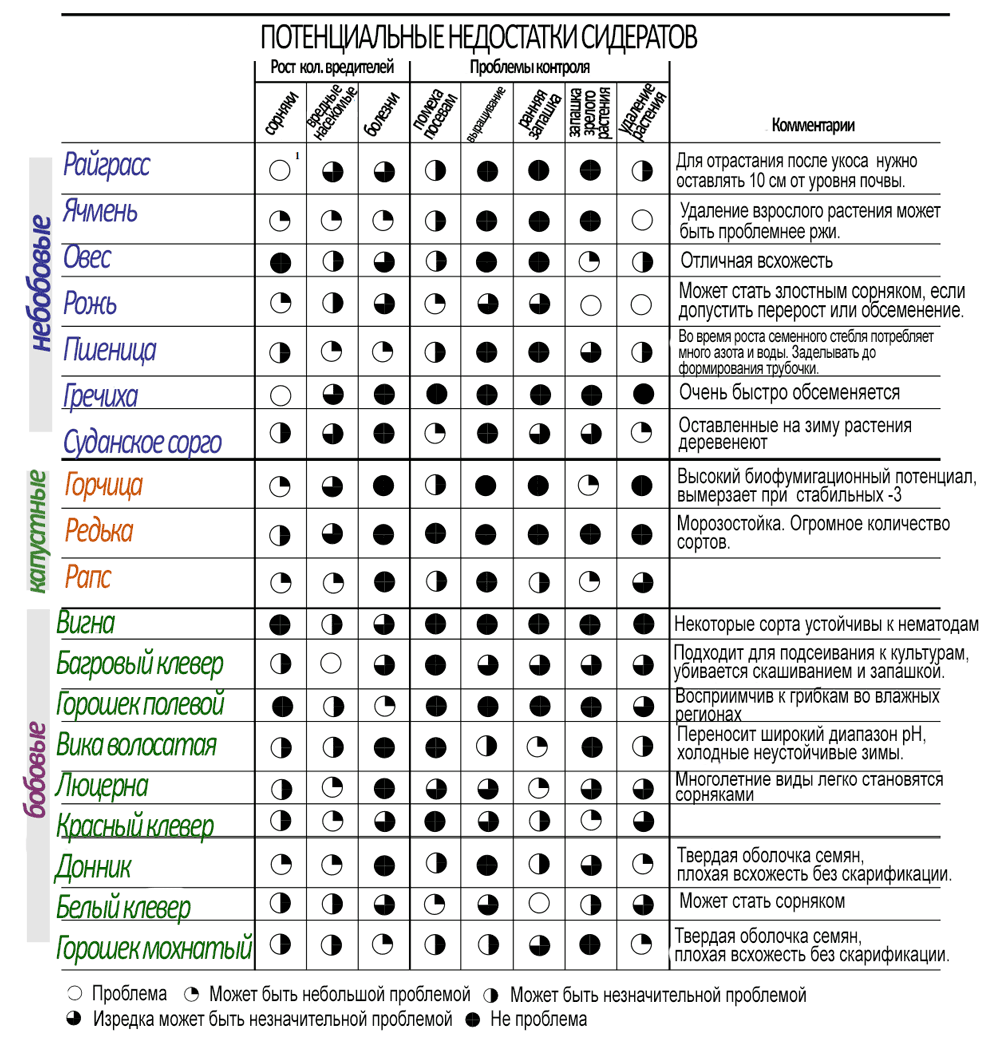

Some of the parameters presented in the table are influenced by seasonality. I kept the original units of measurement (didn’t have the energy to convert them). The nitrogen content in the biomass of non-legumes was not evaluated, so the column remains empty. The chart is explained in detail here .

Traditionally Used Non-Legume Cover Crops Include:

- Annual cereals, both winter and spring (rye, oats, barley, pseudo-cereal buckwheat).

- Annual and perennial forage grasses (ryegrass, sorghum, Sudan grass, and their hybrids).

- Cruciferous plants (mustard, phacelia, oilseed radish, rapeseed, turnip, bok choy, Chinese cabbage, daikon, arugula).

Main Tasks of Non-Legume Cover Crops:

- Partial compensation for nitrogen and mineral losses from the previous crop.

- Prevention of water and wind erosion.

- Accumulation of humus, restoration of soil fertility.

- Weed suppression.

- Live mulching.

Cereal Cover Crops and Grasses

Annual cereal crops are successfully grown as cover crops in many climate zones and farming systems, both as winter and spring varieties. Seeding is done from late August through the fall, depending on the climate. Winter cover crops build good root biomass before frost and start growing greenery earlier than any weeds in the spring.

Grass and other herb biomass contain more carbon than legumes. Due to the high carbon content, grasses decompose more slowly, leading to more effective humus accumulation compared to legume green fertilizers. As grasses mature, the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio increases. Carbon is harder and takes longer for soil bacteria to process, so nutrients from decomposing residues will not be fully available to the next crop. On the other hand, prolonged fertilization has its benefits.

Best Cereal and Grass Cover Crops: barley, oats, ryegrass, rye, buckwheat.

Table Explanation: E - early spring, L - late summer, F - early fall, A - fall, W - winter, S - spring, EL - early summer. C.H. - cold-resistant, T.H. - heat-loving, C.L. - cold-loving. D - direct growing. Resistance: Empty circle - weak, black circle - excellent resistance.

Barley as a Cover Crop

Type: winter and spring. Tasks: erosion prevention, weed suppression, nitrate removal, humus restoration. Mixtures: annual legumes, ryegrass, small-grain cereals.

Barley is a cheap and easy-to-grow cover crop. It controls erosion and weed suppression in semi-arid regions and light soils. It can be included in crop rotations to protect crops and soil from burning out. It cleans saline soils. An excellent choice for restoring contaminated, eroded areas and improving soil aeration. Prefers dry, cool regions.

Barley grows where any other grain fails to build biomass, offering greater forage and nutritional value than oats and wheat. It has a short growing season, combining the benefits of both grasses and cereal green fertilizers. It accumulates more nitrogen than grasses. Contains allelopathic substances to suppress weeds. Research shows that barley significantly reduces the number of leafhoppers, aphids, nematodes, and other pests. Attracts beneficial predatory insects.

Growing: poorly grows on marshy soils, handles drought well. Best grown on loams or light clay soils, performs well on light, dry, alkaline soils. Many barley varieties are adapted to specific climate zones. Can be sown in winter (before November) or spring. Seeding depth of 3 to 6 cm in moist soil. Works well in mixtures with legumes (serves as support for them), and grasses. A proven mixture is oats/barley/peas (organic farmer Jack Lazor, Westfield, VT). White mustard will not grow in a barley mixture, as it is a strong allelopath for crucifers.

Incorporation: like any cereal cover crop, barley should be mowed before heading and immediately incorporated into the soil.

Ryegrass as a Cover Crop

Type: perennial and annual grasses from the Poaceae family. Tasks: erosion prevention, soil drainage and structure improvement, humus accumulation, weed suppression, nutrient accumulation. Mixtures: with legumes and other grasses.

A fast-growing grass that establishes itself almost anywhere with adequate moisture. It accumulates excess nitrogen, protects soil from erosion and weeds, and improves irrigation efficiency. Ryegrass is a good choice for creating a loose, fertile soil layer. It has an extensive, fine root system that establishes quickly in both rocky and overly wet soils. It grows quickly, outcompeting and suppressing weeds. Ryegrass can be mowed, providing mulch for other parts of the garden. It winters well even without snow cover. Ryegrass prevents nitrogen leaching over winter. It attracts few insect pests but may suffer from stem rust and a specific type of nematode (Paratylenchus projectus).

Growing: ryegrass prefers fertile, well-drained loams or sandy soils but thrives on rocky, poor soils as well. Tolerates waterlogging and clay. Sow into loosened soil, the first watering will ensure shallow seed incorporation and good germination. Sow 40 days before the first hard frost. Ryegrass can be overseeded with nightshades when they start flowering. Spring seeding is done after the first early harvest, aiming for 6-8 weeks of growth. Tolerates drought poorly, as well as prolonged extreme temperatures on poor soils.

Incorporation: incorporate ryegrass during flowering; mowing does not kill this plant. Planting crops after ryegrass should be delayed by 2-3 weeks to allow the green mass to decompose and start releasing nitrogen.

Oats as a Green Fertilizer

Type: annual cereal. Tasks: weed suppression, erosion prevention, humus accumulation. Mixtures: clover, peas, vetch, and other legumes and cereals.

An inexpensive, good green fertilizer. Oats quickly build biomass and enhance the productivity of legumes in cover crop mixtures. It mulches gently, protecting the soil from wind and water erosion. Winter oats fix nitrogen after autumn incorporation of legumes, helping them overwinter. It does not attract pests and has allelopathic properties against weeds and some crops when decomposing, so a 2-3 week interval after incorporation is necessary before planting fruit crops.

Growing: sow oats in late August to early September or 40-60 days before the first frost, but it is the least cold-resistant of cereals. For effective germination, there must be sufficient moisture and not too hot conditions, so early spring sowing is more popular among farmers than sowing before winter. Oats can be mowed during growth.

Incorporation: incorporate oats into the soil before heading, cutting the root to 5-7 cm. It decomposes quickly, but a two-week break between incorporation and planting crops is needed due to oats’ allelopathic influence on salads and peas. This cereal is easier to incorporate than rye and decomposes faster.

A few comparative notes: Oats accumulate a lot of potassium and deplete the soil, so incorporation should be done where it is grown to replenish losses. It is less effective in weed, pest suppression, and nitrogen fixation compared to crucifers. Rye is better than oats but more challenging to grow and incorporate. For complementary crops to legumes, oats are the best.

Rye

Type: winter and spring. Tasks: weed suppression, soil structuring, organic matter accumulation, pest control. Mixtures: with legumes and grasses.

Rye is the most resilient of cereals. It has a powerful root system that prevents nitrate leaching. An inexpensive cereal that outperforms other grains in yield and resilience on infertile, acidic, sandy soils. Rye increases potassium concentration in the fertile soil layer, lifting it

from deeper soil layers. It can accumulate up to 30% more potassium than other cereals. It also absorbs more phosphorus.

Growing: can be grown on any soil. Sowing begins in late summer. For winter rye, sowing begins in late August to early September. Spring rye can be sown in early spring but should be sown after any fall tillage, as rye should not be grown as a first crop in spring. Rye thrives in arid conditions but requires good soil moisture in the spring for optimal growth. In colder climates, rye is often sown before winter and removed in the spring, providing good cover during the winter months.

Incorporation: it should be mowed before heading and incorporated into the soil to ensure decomposition and effective green manure.

Buckwheat as a Green Manure

Type: Broad-leaved pseudo-grass. Purpose: Soil mulching, weed suppression, nectar source, soil formation. Mixes: Sorghum-Sudan grass.

Buckwheat as a green manure is a fast-growing crop with a short decomposition period and nitrogen mineralization. It matures in 70-90 days. It attracts pollinators and beneficial predators and is easy to incorporate into the soil. It is the best among grains for phosphorus accumulation and mineralization, with special root exudates that transform soil minerals into a plant-available form. It grows well in moist, cool conditions but is sensitive to drought and overly compacted soil. It thrives on poor, saline soils and cleared land. It’s a renowned nectar source and lure for beneficial predators.

Cultivation: Buckwheat prefers light, medium, sandy loam, loam, and clay soils. It does poorly on limestone. Extreme heat can cause wilting, but buckwheat recovers quickly from short droughts. Buckwheat seeds germinate in three to five days and regrow after mowing. American farmers use a triple buckwheat rotation for virgin or “exhausted” lands and reintroduce them. It flowers a month after planting and continues to bloom for up to 10 weeks.

Incorporation: Buckwheat should be incorporated within 7-10 days of flowering to prevent it from becoming a weed. Note that it seeds unevenly. The biomass decomposes quickly, allowing you to plant crops immediately afterward—no allelopathic effects are observed. Buckwheat is three times more effective than barley in phosphorus accumulation and ten times more effective than rye (rye is the poorest in phosphorus among cereals).

A downside of cereal green manures is their relatively low nitrogen accumulation compared to legumes. Many grasses easily become glyphosate-resistant weeds (selective varieties specifically developed for this resistance). If there is a need to combat glyphosate-resistant grasses, Chlorosulfuron is an option.

Sudan Grass or Sudan Sorghum

Type: Annual plant Purpose: Soil loosener, soil-former, biofumigant. Mixes: Buckwheat, creeping legumes.

Sorghum adds a huge amount of organic matter to the soil when incorporated. This tall, fast-growing, heat-loving annual plant suppresses weeds, controls some types of nematodes, and penetrates deep soil layers. Sudan sorghum is an excellent green manure after harvesting legumes because it consumes a lot of nitrogen. The waxy leaves of Sudan grass are drought-resistant.

Sudan sorghum is a hybrid of two grasses, sorghum and Sudan grass. Both species are used as green manures individually, but the hybrid has a few advantages: drought resistance and frost tolerance.

It has an aggressive root system that aerates the soil. Mowing strengthens and branches out the Sudan grass root by 5-8 times! The stem can reach 4 cm in diameter and grow up to 3 meters tall. Weeds have no chance against such a green manure.

Sorghum produces a special allelopathic substance, sorgoleone, emitted by the roots—a herbicide that competes with synthetic herbicides in concentration and effectiveness. This compound starts to be released on the fifth day after germination. Sorghum’s most effective allelopathic effects are on: bindweed, sundew, field horsetail, green bristly foxtail, pigweed, and ragweed. It also strongly affects crops, so it’s important to maintain a gap between incorporating Sudan grass and planting crops.

Sowing Sudan sorghum on harvested fields is an excellent way to disrupt the life cycle of many diseases, nematodes, and other pests.

Due to its enormous biomass and deep root system, Sudan sorghum restores fertility to depleted and compacted soils within a year. It is the best green manure for draining clayey, wet soils, where heavy machinery has been used. This is widely used by farmers in the northeastern U.S., where frequent rains force them to grow crops on wet land.

Cultivation: It’s best to sow Sudan sorghum in warm, moist soil with a neutral pH. The optimal temperature for rapid growth is 18-20 degrees Celsius. It likes and tolerates summer heat well. Sow seeds to a depth of up to 5 cm, either in rows or scattered. Seed rate is 2 kg per hundred square meters. It is not demanding on soil. Late sowing can be done 2 months before the first frost. Sowing 7 weeks before frost eliminates the need for incorporation, and frost-resistant varieties will continue to grow until severe frosts.

Sow legumes after sorghum-Sudan grass by late summer or in spring to replenish nitrogen. Grow in spring before late crops to allow the green manure to decompose. American farmers plant Sudan grass every third year on potato and onion fields alongside legumes to treat soil for pests and renew humus reserves. Potato yields have been reported to increase. In California, it is sown between grapevines to reduce grape sunburn.

Incorporation: Mowing can be done with a one-month interval. The first mowing should be before the seed heads form when the greenery is juicy and easy to incorporate—when the stem reaches up to 80 cm in height. At this stage, the grass can be fully incorporated. If the Sudan grass is allowed to complete its entire growing period, it will become woody and difficult to incorporate. In this case, let it overwinter—the roots should decompose by 80%. If mowing, the green mass can be used for mulching other beds or added to compost. Mow no lower than 15 cm. One mowing per season is optimal for the plant.

Sudan grass decomposes slowly, especially without incorporation. Nematode control is only possible with the incorporation of fresh green mass before it reaches the tube stage. For controlling wireworms and potato nematodes, rapeseed works better than sorghum-Sudan grass hybrid. Sorghum also has its pests, such as corn aphids.

Some hybrid varieties are not suitable for animal feed due to the presence of prussic acid.

Cruciferous Green Manures

Cruciferous plants meet all the requirements for green manure: they grow quickly, have juicy rich biomass and extensive networks of fine roots, suppress weeds, fungi, wireworms, nematodes, and scab. Some crucifers, like daikon radish, have roots that can penetrate clay layers more effectively than other green manures and, if left to decompose over winter, provide a lot of humus. Mustards are ideal for fixing nitrogen remaining after harvest as they quickly accumulate green mass. Without green manure, this nitrogen would be lost as ammonia, but mustard returns it to the soil along with other nutrients.

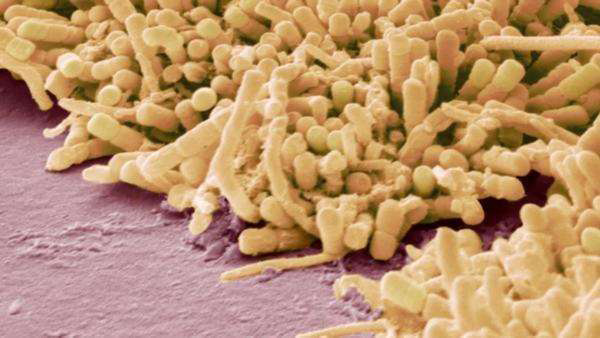

Pest suppression is likely related to the breakdown of glucosinolates (neurotoxins responsible for the mustard taste) into thiocyanates, which are used as insecticides and seed treatments ( link to the study). Mustard sown with rapeseed works more effectively. Many positive observations have been documented by American soil scientists, with references in this book. Compared to ready-made solutions, green manure fumigation is weaker, so don’t rely solely on green manures to control pests.

Weed suppression and control with cruciferous green manures are related to rapid growth and “canopy closure,” meaning their high cover ability. The allelopathic effects of decomposing residues incorporated in the fall also play a significant role. Mustard and oilseed radish prevent the development of shepherd’s purse, pigweed (amaranth or lamb’s quarters), bristly foxtail, dock, knotweed, field horsetail, and more.

Cultivation: Most cruciferous plants grow well in well-drained soils with acidity levels of 5.5-8.5. Too wet soil, especially during rooting, is unacceptable (rye handles this much better). Fall sowing should be done as early as possible, but the general rule is no later than 4 weeks before frost. The soil should not be colder than 7 degrees Celsius during sowing and the following week. Some winter rapes tolerate temperatures down to -10 degrees Celsius and continue to grow.

Mustard can be undersown with legumes when they are already established; sowing in mixtures is not advisable as cruciferous green manures can outpace other plants and hinder their development. Traditionally, we sow white mustard, but American research often features mixtures of white and brown mustard, with a higher proportion of brown.

Incorporation: Cruciferous green manures can be incorporated at any growth stage, but the optimal time is early to mid-flowering when the plant reaches maximum biomass. Excess can always be added to compost. Incorporating mustard late in the fall will start to release nitrogen in early spring, just in time for planting the first crops.

Cabbages and mustards require additional nitrogen and sulfur. Why sulfur? Plants use it to

produce essential oils-fungicides and glucosinolates. The optimal sulfur to nitrogen ratio is 1:7 for all cruciferous plants. I previously noted that mineral fertilizers are best applied under green manures, as they return the accumulated nutrients in chelated form (a trendy term, but relevant here). Turnips and radishes accumulate phosphorus and make it more available through root exudates.

Incorporating mustard late in the fall will start to release nitrogen in early spring, just in time for planting the first crops. In terms of carbon content and decomposition rate, cruciferous plants fall between cereals and legumes.

Disadvantages of Cruciferous Green Manures

The main problem with cruciferous green manures is their inability to resist the cruciferous flea beetle. Common diseases affecting fruit cabbages impose limitations on planting cruciferous green manures.

Black mustard has low germination rates and, after stratification, may sprout the following year—becoming a weed. Rapeseed contains erucic acid and glucosinolates that can cause digestive issues in animals. Although breeding has reduced erucic acid content to 2%, rapeseed should not be grown for livestock. Winter rapeseed attracts certain types of nematodes that overwinter in its roots.

You might find the article Which Green Manure is Best and How to Choose It helpful for choosing the optimal green manure or mixture.

References

This overview is based on materials from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, USDA, and the Sustainable Agriculture program at the University of Maryland. I rely on their resources because each statement is supported by research references available for review, and most books are freely accessible. You can email the farmer conducting fieldwork with any questions. This does not mean “the final truth,” but I really appreciate this approach.